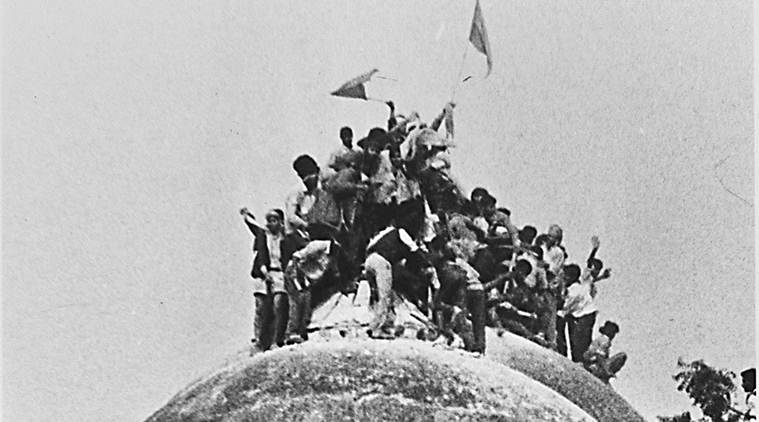

Babri demolition, 1992, involves us all. It was an attack on idea and promise enshrined in India’s Constitution.

“I was part of the political leadership that could see that concerted attempts were being made to pose a challenge to the “secular consensus” by the BJP.”

“I was part of the political leadership that could see that concerted attempts were being made to pose a challenge to the “secular consensus” by the BJP.”

From the vantage point of the 25th anniversary of the Babri Masjid demolition, I can only marvel at the gargantuan shift in the fundamentals of the nation. Beginning from somewhere in the middle 1980s, I have seen the striking change in political developments significantly altering the spirit and the structures on which Indian nationalism had been founded. The political conjuncture of the years, 1989-92, constitutes a moment of rupture in contemporary Indian history. At one end, it saw the complete collapse of the “consensus” which was considered to be enshrined in secularism, socialism and a plural democratic polity.

And on the other end, we saw the triumphant rise of a Hindu right which has culminated as the most dominant force in the political discourse of present-day India. Beginning in the late 1980s, Indian politics has seen the sudden rise of the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) and the ascendance of a Hindu nationalist ideology. Moving from two to 85 parliamentary seats between 1984 and 1989, the Hindu right-wing party was catapulted onto the national political map, where it remained as the ruling party at the national level until May 2004. In a majority since 2014, it has posed the most comprehensive challenge to the secular-socialist fabric in India’s post-Independence history.

I was part of the political leadership that could see that concerted attempts were being made to pose a challenge to the “secular consensus” by the BJP and its ideological affiliates from the Sangh Parivar. I distinctly remember that in the National Integration Council meeting held days before the unfortunate demolition, L.K. Advaniji had assured the members that nothing shall happen to the mosque. In view of the massive communal-sectarian mobilisation all over north and western India, some of us had no reason to believe his words. In fact, we urged the Central government to send the army to Ayodhya-Faizabad. However, the then Central government apparently went by the assurance of BJP veterans and thus a 400 year-old mosque was demolished 25 years ago in 1992.

This event also initiated a new phase of sectarian violence and the targeting of the minorities, especially Muslims, in several cities across India. As the then chief minister of Bihar, I knew my priorities, and the combined strength of the people, administration and political will made sure that no episode of violence was reported in the state. However, the demolition constituted the first event that unequivocally conveyed that it was not simply an onslaught on a mosque but on the very idea of the rule of law upheld by a republican constitution.

In order to have a comprehensive understanding of why the Sangh Parivar and its outfits decided to go for mass mobilisation in the name of the Ram temple at Ayodhya, we need to look at August 1990 as the watershed moment for the backward and vulnerable sections of Indian society. The implementation of the Mandal Commission recommendations in 1990, providing for affirmative action for OBCs and the violent battles fought around the same, aimed at permanently altering the narrative of Indian politics. We could see the consolidation around this event, and a wide range of political parties articulating the concerns of Dalits and backward castes emerged as significant players in Indian politics. The assertion of backward classes rattled the Sangh Parivar which took inspiration from the exclusivist Manuvadi paradigm of M.S. Golwalkar conveyed through his book Bunch of Thoughts.

They knew at the core of their hearts that the subaltern consolidation across India in the wake of the Mandal commission’s implementation shall provide them with no space in the political arena. Thus, orchestrated campaigns like the shila pujan were a desperate attempt to counter the challenge posed by the awakening of the poor and the downtrodden. The mobilisation had nothing to do with Lord Ram, the Maryada Purushottam, but was meant to thwart the consolidation of the backward classes post-Mandal and stay relevant in politics by mixing faith with politics. They were partially successful when, following the destruction of the Babri mosque (1992), the Bombay riots (1993) and the establishment of a BJP-led coalition government (1998) soon followed.

However, India in 2017, after two decades and-a-half appears significantly changed from the India of 1992. During the ‘90s, we saw that the majoritarian mobilisation stood in strong contrast to the democratic churning of diverse, erstwhile marginalised groups on the political map. It was also observed that extremist forces, despite their capacity to wreck the social equilibrium on emotive issues, remained peripheral to India’s basic socio-political fabric firmly grounded on a well-entrenched pluralistic ethos. Though the 1992 Babri masjid demolition was illustrative of attempts to divide Indians on a singular identity, that is, religion, the political forces that spearheaded the campaign for Hindu consolidation remained peripheral in India, which was reflected in the loss of the BJP in the 2004 general elections and the subsequent victory of the United Progressive Alliance (UPA) in 2009.

What is most worrying about present-day India is that there is a marked shift in the political discourse, where there is not only greater acceptability of the idea of a “majoritarian homogenous cultural nationhood” but also the relegation of minorities and other vulnerable groups to the status of “non-citizens”. The brazen forms of majoritarian violence being unleashed on the people and communities on the margins through mob lynchings, cow vigilantism and religious assertions by the majority, are reflective of the transition India has undergone from the 1990s to the post-2014 political landscape.

This transition is also reflected in the political discourse. The entire discussion over the demolition of the Babri masjid has been repositioned as merely a dispute between two communities and a title suit over the land where the Babri masjid once stood. As somebody who has lived through these turbulent phases of history, I believe we must not hyphenate the Babri masjid demolition with Muslims alone. It was an attack on the very idea of “We the people”, the opening lines of our Preamble.

We are standing at a juncture in Indian democracy that might head towards the severe erosion of its pluralist character if we do not re-build a consensus all over again — that differences in opinion, faith, values, beliefs, and attitudes have to be accommodated and appreciated rather than suppressed. Twenty-five years later, the demolished medieval mosque seeks an answer from all of us: Will the India of Bapu’s dreams remain, or will it succumb to pressures from the ideology that assassinated him?