Peace Now: No Nukes Over South Asia

In the past twenty years since the nuclear weapons tests by India and Pakistan, both countries have sunk into deeper social crises and seen the rise of inequality, militarization, and religious nationalism, creating an urgent threat to peace in the subcontinent and security in the world. Four prominent public intellectuals from Pakistan and India will address a public forum on matters that have engaged them in their work on democracy, human rights, pluralism, freedom of expression, and peace.

Panel:

Zia Mian: The Nuclear Danger in South Asia

A. H. Nayyar: Building Peace Under the Nuclear Shadow

Rammanohar Reddy: Crisis of Democracy and the Assault on the Media

Achin Vanaik: Nationalism, Democracy, Internationalism

Moderator: Haider Nizamani

The panel will be followed by a film: Pakistan and India Under the Nuclear Shadow (33 minutes)

Speaker profiles:

Zia Mian is a physicist, activist and co-director of Princeton University’s Program on Science and Global Security, which is part of the Woodrow Wilson School of Public and International Affairs. His research and teaching focuses on nuclear weapons and nuclear energy policy. He is co-chair of the International Panel on Fissile Materials (IPFM), a group of independent experts from eighteen countries working to reduce global stockpiles of nuclear weapon-useable material. He serves on the board of the Arms Control Association and previously served on the board of Peace Action, the largest US grassroots peace network. He received the 2014 Linus Pauling Legacy Award for “his accomplishments as a scientist and as a peace activist in contributing to the global effort for nuclear disarmament and for a more peaceful world. In 2018, he was selected as one of the “60 faces of CND” by the UK Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament to mark its 60th anniversary.

Dr. Abdul Hameed Nayyar is a physicist who retired from Quaid-e-Azam University Islamabad after serving it for over 30 years. He has a PhD in theoretical condensed matter physics from Imperil College London. He has worked extensively on the technical analysis of nuclear disarmament issues and associated with programs that provide education to children of disadvantaged sections of the society. Dr. Nayyar is a member of the International Panel on Fissile Materials and was awarded the 2010 Joseph A. Burton Award from the American Physical Society. He has participated in national, regional and international anti-nuclear peace movements and served as President of the Pakistan Peace Coalition, and was a founding member of the Asian Peace Alliance.

C. Rammanohar Reddy has a Ph.D. in Economics but has been in journalism since 1988. He is currently Readers’ Editor at Scroll.in. He was earlier Editor of ‘Economic and Political Weekly’ (2004-16). With MV Ramana he co-edited “Prisoners of the Nuclear Dream” (Orient Longman, 2003). He is the author of “Demonetisation and Black Money” (2017).

Achin Vanaik is a retired Professor of “International Relations and Global Politics” in the Political Science Department of Delhi University. He has authored or coauthored or edited or co-edited 10 books ranging from studies on contemporary India’s politics/economy/foreign policy to matters of religion, secularism, communalism and nationalism to issues of international politics and nuclear disarmament. He has been actively involved in various civil liberties and anti-communal activities and is a founder-member of the Coalition for Nuclear Disarmament and Peace (CNDP), India. He has been a Fellow of the Transnational Institute based in Amsterdam from 1988 onwards and has served twice on the Board of Executives of Greenpeace India. Along with Praful Bidwai, he was awarded the Sean MacBride International Peace Prize for the year 2000.

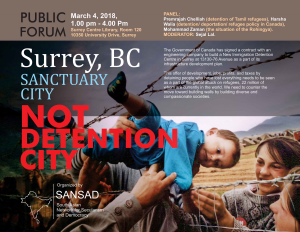

Organized by South Asian Network forSecularism and Democracy (SANSAD). Co-sponsored by the Institute for the Humanities, SFU, South Asian Film Education Society (SAFES), and Committee of Progressive Pakistani Canadians (CPPC). Speakers courtesy of the School of Public Policy and Global Affairs, UBC.

Date: May 26, 2018 (Saturday), 2 to 5 PM

Venue: Room 7000, Harbour Centre, Simon Fraser University, 515 W Hastings St, Vancouver, BC V6B 5K3

Video record of the event: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=CyG1s4Qwajo

The formidable human rights lawyer and activist died on Sunday having spent her life fighting against religious extremism and for the rights of women and oppressed minorities

She stood a smidgen over 5ft and had fine, delicate bones. But the bird-like frame contained a courageous heart, an indomitable will and an unflagging social conscience. The death of Asma Jahangir, the Pakistani activist, lawyer and human rights campaigner who passed away on Sunday after suffering a cardiac arrest at her home in Lahore, has left a nation reeling with a profound sense of loss.

Looking through social media I am not surprised by the number of tributes to her, but by the fact that they come from her detractors as well as her supporters. The conservatives who branded her a traitor until last week are now acknowledging her courage. Whether that is out of political expediency or genuine feeling I cannot say. But for the besieged liberal community and the religious minorities of Pakistan, she was indispensable. When plainclothes security men barrelled into my sister’s home one night in 1999, dragging away my journalist brother-in-law at gunpoint, the first person she called was Asma. That’s how it was. If you wanted someone in your corner, you called Asma. And she would respond at once.

When I heard the news of her death, my first thought, regrettably, was for myself: “Who will have our backs now?” I was not the only one. A legal watchdog and a political fighter, Jahangir patrolled the rights of secular liberals, religious minorities, the politically disenfranchised, wronged women, abused children; she even fought for the constitutional rights of the very same religious extremists and hard-right nationalists who would have had her silenced.

Jahangir was six years old when her politician father, Malik Ghulam Jilani, opposed Ayub Khan’s martial law in 1958. In 1971, when her father was arrested by another military dictator, Yahya Khan, the teenage girl filed a petition for his release in the Lahore high court: Asma Jilani v the government of the Punjab.

“Courts were not new to me,” she joked with her customary levity. “Even before his detention, my father was fighting many cases. He remained in jail in Multan. He remained in jail in Bannu. But we were not allowed to go see him there. We always saw him in courts. So for me, the courts were a place where you dressed up to see your father. It had a very nice feeling to it.”

The Lahore high court dismissed her petition. Undaunted, Jahangir appealed to the supreme court. In 1972, after Khan’s dictatorship had ended, the court decided it had been illegal and declared him a usurper. Jahangir had won her first case.

She began her legal career as a family lawyer. In 1980, along with her sister Hina Jilani and two friends, she set up a firm specialising in divorce, maintenance payments and custodial cases. It was her work with women that brought her to politics. She realised early on that while it was important to fight for oppressed individuals, what was needed was institutional reform and societal change. So when Zia ul-Haq, Pakistan’s third military dictator, amended the constitution to discriminate against women and religious minorities under the guise of an Islamising agenda, Jahangir publicly challenged his ordinance, questioning its moral underpinnings. He was a brutal dictator with a taste for public floggings who responded by slapping a blasphemy case against her, yet she did not shy away from the fight. Many years later, she wrote: “We may fight terrorism through brute force, but the terror that is unleashed in the name of religion can only be challenged through moral courage.”

She was never lacking in that moral courage. Or in the energy required to pursue the goals she set herself. The list of her accomplishments goes on and on. A founder member of Women’s Action Forum and of the Human Rights Commission of Pakistan; a long-serving UN special rapporteur on human rights; the first woman president of the Supreme Court Bar Association. She opened the first legal aid centre and refuge for battered women in Pakistan. She took on cases that nobody else would touch. She fought for poor Christians accused of blasphemy, a crime punishable by death, but which also put their defenders at risk of assassination at the hands of religious fanatics. In representing bonded labourers, she fought against institutionalised slavery, and in speaking for girls who wanted to marry of their own choice, took on centuries of misogynistic custom, earning the wrath of mullahs, urbane senators and tribal leaders alike.

What rattled her nationalist detractors the most was her consistent critique of human rights abuses in Pakistan. They labelled her a traitor and accused her of being an Indian spy or an American agent. Why couldn’t she highlight similar abuses in other countries? Why must she spread negative propaganda against Pakistan? The fact was that she did call out human rights abuses wherever she found them. She alerted the world to the plight of the Rohingyas, the Palestinians and the Kashmiris, but she was most exercised by atrocities at home. As she said in one interview: “I think it sounds very hollow if I keep talking about the rights of Kashmiris, but do not talk about the rights of a woman in Lahore who is battered to death.”

Jahangir fought on many fronts, but perhaps her greatest ire was reserved for religious extremists and military dictators. She lampooned mullahs mercilessly, mocking their frizzy beards and fuzzy thinking. When other activists called out the ISI, Pakistan’s feared intelligence service, they did so cautiously, referring to it as “the deep state”, “the establishment” or “the powers that be”, knowing what every schoolchild in Pakistan knows: forced disappearances are a fact of life. But Jahangir alone had the courage to go on live television and say: “These duffers, these duffer generals … need to return to their barracks and stay there.” Her commitment to democracy was unwavering. She knew that however corrupt, venal or inefficient civilian leaders might be, they were always preferable to military dictators. “However flawed democracy is,” she told the New Yorker, “it is still the only answer.”

But while others in her place might have lain low for a while or quietly left the country for a spot of “family time”, Jahangir’s response was to go on the front foot. In 2012, she publicly accused intelligence and security agencies of trying to kill her and in so doing turned the spotlight on them. If there was one thing that made her anxious, it was the safety of her three children, whom she eventually sent abroad. But for herself, there was no question of going anywhere. She stayed in Lahore right till the very end, fighting the good fight.