Indianexpress.com

Gurmehar Kaur’s retraction of campaign shows how women who voice dissent are gagged in India

From Kaur to Zaira Wasim, those who’ve challenged authority or seemed to have ‘displeased’ it, have received hate threats and been forced into submission

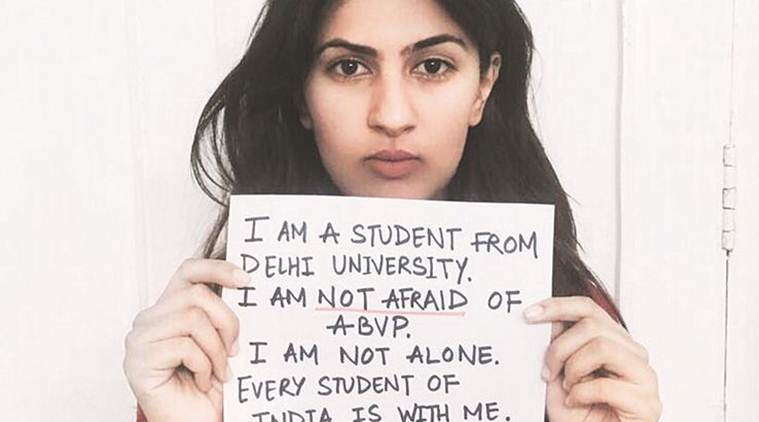

20-year-old Gurmehar Kaur

20-year-old Gurmehar Kaur

Let’s cut through the chase and not call ourselves a “democracy” anymore. Let’s put a lid on the debate regarding this so-called “freedom of expression” we proudly claim to have – for when it comes voicing dissent, we are the first to jump to quell it. Particularly when the dissent comes from a woman. Past incidents hold evidence that whenever women in India have tried to voice an opinion, which have contradicted or clashed with the opinion held by right-wing political authorities, women have been held by the collar and verbally beaten down into silence.

WATCH | Gurmehar Kaur Withdraws Save DU Campaign: Here’s What Happened

When Gurmehar Kaur raised her voice against the appalling violence spawned, stirred and inflicted allegedly by the ABVP (RSS’ political student arm) in Delhi University last week, she did it in the simplest, hard-hitting manner. Her activism – of a mug shot with a placard stating: “I am a student from Delhi University. I am not afraid of ABVP. I am not alone. Every student of India is with me. #StudentsAgainstABVP” – did not defame ABVP. The language in the message was not anchored in ridicule or abuse. All it did was challenge ABVP’s authority.

Kaur’s message – the vortex of her political activism – spiraled into a viral storm. It fulminated a backlash from right-wing conservatives, of colossal proportions, against her. Troll messages grounded in disturbing, unfounded misogyny, ricocheted off her Twitter page.

Kaur went on record to say that she received rape threats.

Rape has been used as the universal instrument to subjugate, silence and conquer women. In patriarchal societies, women asserting themselves has been viewed as toppling the ‘norm.’ The only way to maintain the norm, is to rein in their tongues. Instilling a paralyzing sense of fear through rape, or rape threats, is the most convenient and preferred modus operandi for those who wish to uphold the patriarchal order. Violating a woman’s body violates her identity and her sense of being. You trample over that and she’s conquered, quietened down. The only way to control her – is to sexually humiliate her.

WATCH | Virender Sehwag Tweets Following Kargil Martyr’s Daughter’s Anti-ABVP Post

What is disappointing is that it works. Kaur retracted from her #SaveDU campaign today on Twitter saying, “I’m withdrawing… Congratulations everyone. I request to be left alone. I said what I had to say.. I have been through a lot and this is all my 20 year self could take :)”.

Kaur is not alone. A little over a month ago, sixteen-year-old Zaira Wasim, who performed the role of wrestler Geeta Phogat in Dangal, was publicly berated on Twitter for meeting Jammu and Kashmir Chief Minister Mehbooba Mufti. Wasim received countless death threats from Islamic conservatives, which bullied her into publishing an apology on a social platform. “I know that many people have been offended and displeased by my recent actions or by the people I have recently met,” she wrote in January. “I want to apologise to all those people who I’ve unintentionally hurt and want them to know that I understand their sentiments, especially considering what has happened (in Kashmir) over the past six months.”

Then of course, there was the all-girl’s rock band called Praagaash (From Darkness to Light) from Jammu and Kashmir, which disbanded in 2013 after a Muslim cleric issued a fatwa against them saying it was “un-Islamic” for teenage girls to sing in front of unknown men in public spaces. The girls were diabolically trolled on social media, receiving multiple rape threats.

WATCH VIDEO | Olympian Wrestler Yogeshwar Dutt Tweets Against Gurmehar Kaur

Kaur’s withdrawal, Wasim’s apology, Praagaash’s disbanding are indicators of forced submission; a push to align to the norm maintained a male-reigned world. Disconcertingly, their submission perpetuates the age-old narrative, that through threats steeped in violence, particularly rape, women can be gagged.

Last year, JNU student and activist Shela Rashid received rape threats when she participated in a protest opposing a seminar by Yoga guru Ramdev in JNU on Vedanta. The protest led the seminar to be cancelled but Rashid got a letter addressed directly to her. ‘The letter, written anonymously, called me everything under the sun…. I have been trolled and abused by people on Twitter, and I have learnt to ignore them. But this letter tried to create a fear psychosis,” Rashid had told The Telegraph in 2016. She too, had noted that such threats were used to control women: “This is a threat of physical abuse. This is not just about one letter, it is about broader women’s issues. The kind of language used in the letter or the rape threats on social networking sites against women deter them from entering public spaces. It also forces women who oppose to shut up.”

In the midst of bellicosity launched against Kaur – primarily by men – her older messages have been excavated. Daughter of a soldier who died fighting in Kashmir, Kaur back in April 2016, had released another string of placard messages that described her stance against war. However, one particular message from her campaign – “Pakistan did not kill my dad. War did” – has been strategically pulled out of context and is being looked at in isolation.

Union Minister of State for Home Affairs Kiren Rijiju asked who had been “polluting” Kaur’s mind. Actor Randeep Hooda too, went ahead and ridiculed Kaur, saying that she was a “poor girl” being used as a “political pawn” by political leftists.

WATCH |Randeep Hooda Writes An Open Letter After Being Accused Of Trolling Kargil Martyr’s Daughter

Two important, troubling things emerge in this context: One, that a woman cannot build or have her own political opinion – if she does, she has been “taught”. It trivializes not only a woman’s right to voice her opinion, but also her ability to build one. Disappointingly, Kaur has been man-interrupted for her views, because no one saw the context of her older campaign relating to her comment on war. At that time, the intent of her campaign was not one that supported Pakistan, but one that supported peace. It was a message aimed at both Indian and Pakistani governments, requesting them to not embroil in wars, because countless fathers were lost in such ordeals.

Here’s the larger point to think about though: If we, as Indians, threaten to rape our own women under the garb of nationalism, then we carry an alarmingly warped sense of nationalism. Our definition of nationalism is being disintegrated into a despicable charade and no one is doing anything about it.

While there have been the likes of many, like Javed Akhtar, who have voiced solidarity with Kaur, the unfortunate reality of things persists: women who voice dissent will be gagged or pushed into a corner to retract. And that’s what happened with Gurmehar Kaur today.