dw.com

INDIA

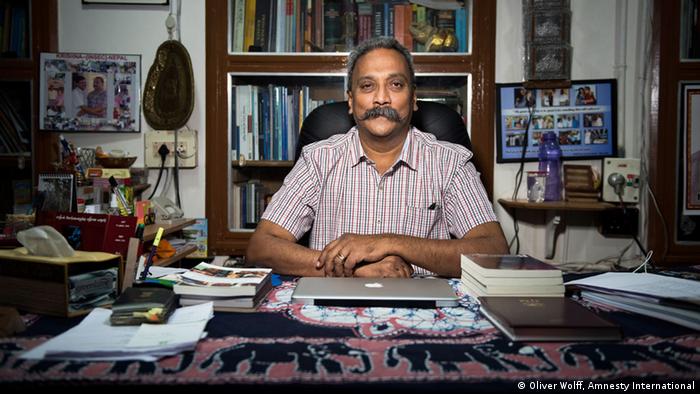

Tiphagne: Biggest challenge is ‘criminalization’ of human rights work in India

Indian activist Henri Tiphagne is set to receive Amnesty International Germany’s human rights award in Berlin on Monday. DW spoke to him about his work and the obstacles faced by rights groups in India.

DW: How do you feel about receiving Amnesty International Germany’s human rights award? What does it mean for you and your work?

Henri Tiphagne: In the field of human rights, generally, one never receives awards and rewards. And so it was a real surprise. I am, therefore, receiving this award on behalf of a number of my mentors, largely from India, who worked for human rights and died without any awards.

I also think this award is being handed over to an individual on behalf of a number of human rights defenders across India, whose names, faces and work are unknown to many globally.

These people have had to face many challenges and pay the price in various forms for having stood for the protection of human rights. It is on their behalf that I receive this award.

What inspired you to become a human rights activist?

My journey as an activist started in the 1970s, when I was in university and understood the need for better social justice in society. And it is this longing for social justice for the poorest of the poor in society that gradually translated itself into work for human rights.

I would also say that my mother, who came from France as a single woman to serve leprosy patients in India and adopted me, and the service that she did drew me into this quest for justice.

And later, the All India Catholic University Federation molded me and played an important role in my transformation into a human rights defender. This is the basis of my work today.

Tiphagne: ‘The government is resorting to the use of various legal provisions to create hassles and curtail the work of human rights defenders’

Tiphagne: ‘The government is resorting to the use of various legal provisions to create hassles and curtail the work of human rights defenders’

What are the major obstacles faced by human rights activists in India?

The challenges that are faced by human rights defenders in India are plenty. The first and the most important is the criminalization of human rights work, for instance, by registering a series of false cases. If you are protesting, registering dissent, critical of government policies, then the first thing that is done is to file a slew of false cases against you.

The falsity of the cases is evident from the type of cases registered – sedition, armed revolt against the state, waging war against the state.

The second problem they face relates to torture – both psychological and physical. A variety of means are used to threaten people and discourage them from carrying on with the work they are doing.

The third challenge, particularly for women, is attempts to discredit them and their work. Moreover, sexual overtones are brought into their human rights engagement in a variety of ways. And in addition to being discredited, their dignity is lost by the kind of allegations that are spread against them.

Today, the Indian government is also resorting to the use of various legal provisions to create hassles and curtail the work of human rights defenders. The major problems we face are mainly related to our rights to association, expression and assembly.

I would agree with those critics, but I would like to point out that this restriction of space for civil society organizations even preceded the Narendra Modi government. Similar restrictions were imposed even during the previous Congress-led government.

It would, therefore, be wrong for me to put the entire blame on the present government, as the present government inherited these tendencies from the previous one.

However, it is important to categorically state that the present government has tightened the restrictions to a very high level, and as a result, there is total intolerance in the country, which is exhibited in a variety of ways.

What needs to be done to improve the working conditions faced by NGOs and activists in the country?

Firstly, we are a country of institutions. India is the only country globally which has about 169 national and state human rights institutions. But the government has failed in ensuring the independence of all the institutions it has created.

It is these institutions, therefore, led by the National Human Rights Commission (NHRC), which should immediately intervene and ensure that space for the right to association, assembly and expression of human rights defenders through civil society organizations is protected.

Secondly, the government has to recognize that it is obligated, by virtue of all the conventions and protocols it has signed, to ensure that the UN principles and guidelines for protecting the rights of human rights defenders are respected within the country. I think these are two urgent things to be done.

Also, we don’t have a ministry of human rights, and we don’t have a parliamentary committee on human rights. We need a ministry which caters to human rights, and a parliamentary committee which delves into the issue of human rights, thus making it a vibrant subject within our polity. Both our government and parliament, and not only the judiciary, have a very important role in ensuring this.

Will the Amnesty award change your work in any way?

The award, I think, is an opportunity for me to appeal to a larger number of people in India, to companies engaged in economic activities in the country, and a number of well-meaning individuals who respect the constitution and are proud to be Indians, that citizens groups like our organization need appreciation, support, solidarity and financial resources from the Indian public and companies.

We need a large number of people to contribute by supporting us with small amounts, thus making us accountable on a regular basis and transparent to this large number of people who will be supporting us. In this way, we will become a powerful organization, but always answerable to all those who support us and make us a really rooted Indian organization.

And, I think, this award is going to give us the space to be able to do that, in particular.

Henri Tiphagne is Executive Director of People’s Watch Tamil Nadu, a leading India-based NGO. He receives Amnesty International Germany’s human rights award at the Maxim Gorki Theater in Berlin on Monday, April 25, as a recognition of his commitment to human rights.

- Date 25.04.2016

- Author Interview: Srinivas Mozumdaru